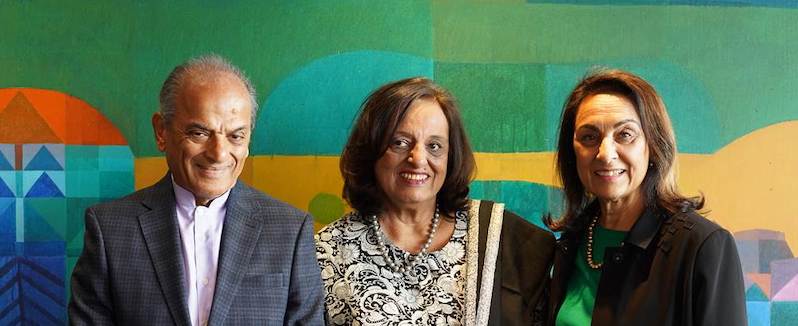

Ranjit Mathrani chairs MW Eat, the highly influential London group whose first restaurant, Chutney Mary, opened 35 years ago this month. A former senior civil servant and merchant banker, he runs the company alongside his wife Namita Panjabi (right in photo), the first Indian woman to become a merchant banker, and her sister Camellia Panjabi (centre), a former director of the Taj Group and author of the all-time best-selling Indian cookbook, ‘50 Great Curries of India’.

Ranjit spoke to Harden’s soon after news broke that Veeraswamy, London’s original and most distinguished Indian restaurant, owned by MW since 1997, faces possible closure ahead of its centenary next year because the Crown Estate plans to kick it out of its premises in Regent Street in order to renovate the offices above.

HARDEN’S: Ranjit, thank you for taking the time to speak to us. To start with, can you tell us about the legal battle with the Crown Estate: it seems odd that a body whose beneficiary is itself a heritage entity – the monarchy – is prepared to destroy a piece of cultural history just to improve some office facilities. And surely there’s a business case that leisure, hospitality and tourism are the lifeblood of the West End anyway.

Ranjit Mathrani: The whole thing is baffling. As someone who worked in government for 18 years, I find myself wondering, ‘Are these people serious?’ The only explanation I can think of is that middle-level people at the Crown Estate have become so blinkered that they can’t see the situation in full – they’ve come to the view that our restaurant is inconvenient, an irritation, and that making compromises for the sake of history is a bore.

But I want to reassure everyone that Veeraswamy is not going to close down. We are fighting the matter in the courts. Our legal case is very strong. However, we prefer to reach agreement. We’ll work something out. People waste a lot of time and energy planning for eventualities that never happen, so we’re not planning for a worst-case scenario now – we’ll face that if and when it happens. In the mean time, I hope everyone will sign our petition on change.org.

The three of you each had your own high-powered careers before you opened Chutney Mary. What prompted the move into restaurants?

The idea for Chutney Mary came from discussions around the dinner table with Namita and Camellia. Camellia had launched the Bombay Brasserie for the Taj Group in Kensington, and it became the most famous Indian restaurant in the world. She is incredibly talented and creative – but the reward went to the corporation rather than the creator.

So I thought, why don’t we open a restaurant on ‘sweat equity’ lines – the approach that has made so many of the tech guys in Silicon Valley rich. The creative talent earns a portion of the business through their contribution.

My role was to raise the money – I would never have had that idea if I had not been a merchant banker. So Neville Abraham of Chez Gerard, who were our sweat equity partners, and I found 60 investors who each invested £10,000, £20,000 or £30,000. Namita and Neville ran Chutney Mary for the first six years. We then bought them out and I became involved.

What was so different about Chutney Mary – and what made it successful?

It was the first non-European restaurant in the world to have a serious wine list. This was partly because Neville had originally created Les Amis du Vin. And it also reflected my own background and tastes, as an upper-middle-class professional living and working in the west, laying down good claret and eating in sophisticated restaurants – so mainly French food.

Serving Champagne and good wine was important to us, to wean people away from the idea that you have to drink beer with Indian food. But you can’t really match great wine with Indian cooking in the way that you can with individual French dishes – you have to cleanse the palate with a sip of water before you drink top wines.

What else were you able to bring to the project?

As an investment banker, you spend a lot of time in good restaurants entertaining clients, negotiating contracts, discussing business. You’re working too hard to really enjoy the quality of the cooking – but one thing you do notice is service.

So my contribution from an operational perspective was to see a restaurant from the consumer’s point of view. I was riveted by American standards of service, which I had experienced for example at Danny Meyer’s Union Square Café in New York. In Britain standards are nowhere near as good as they should be – in America, they really think about the customer experience, everywhere from McDonalds and KFC to fine-dining.

After service, my other big passion is visual style. Running a restaurant, you have to be aware that you are asking for your customers’ money and time – both precious commodities. So whatever you do has to give them the sense that they are getting value, not just in food, but in the whole experience.

That is why design is so important. Eating out is an escape from the everyday world, into an experience people can’t have at home. You can’t let people get bored. On this, my view is a complete reverse of the classical French restaurant, with white tablecloths and so on.

You also have to be open to change. At Chutney Mary, we have completely redone the interior four times in 35 years (including the change of address from Chelsea to St James’s). However loyal your customers are, they don’t want to go back to a place embalmed in aspic. Relentless reimagination is just as relevant as the original idea – you have to remain analytical, and stay one step ahead of important trends.

My third passion is to ensure we combine high quality of food, service and design with being a profitable, professionally managed business – to be good at everything we do as a business.

How did you come to acquire Veeraswamy?

We were thinking of opening a second restaurant when we heard that Veeraswamy was being sold. It had been in decline for a while, and had not adapted to the arrival of Chutney Mary and Bombay Brasserie – it had become embalmed in aspic (a favourite phrase of mine!).

So we made contact, and I was told that if we could exchange contracts in one week, it was ours. And because of my background in merchant banking, we could do this – I took a view that it was worth taking a calculated risk to cut through the whole due diligence process.

Ironically, Veeraswamy is the historical reason why people in Britain drink beer with curry. In the 1920s and ‘30s, it was one of the top five restaurants in London irrespective of cuisine, along with The Ritz and Pruniers (whose premises now house Chutney Mary). The ruling classes of India would visit when they were in London to get their fix of spice.

It’s close to Buckingham Palace, and the Prince of Wales used to come too – he introduced the Prince of Denmark, who decided he wanted to drink Carlsberg with his curry, and sent a barrel. And that’s how the practice started.

Amaya was also very influential, probably more so than people realise – it kicked off the now-familiar trend of open-kitchen grill restaurants serving sharing plates. How did that come about?

As far back as 1989, the three of us were sitting around the dinner table again. We were talking about Indian food beyond curry – lighter dishes – and I had liked Michel Guérard’s ‘cuisine minceur’. We put the two of them together and realised that the grill cooking of the NorthWest Frontier fitted, along with seafood barbecues on the coast.

Much later, in 2003, we were looking to open a new restaurant, and premises came up in Knightsbridge that we knew suited this style of cooking – and we had six weeks to make it happen. Talking it through with Camellia, we realised that we needed to break barriers in how people perceived Indian food.

It was Camellia’s vision that we clear that we had to show that all the food was fresh-made – and the best way to do that was to be completely transparent, with an open kitchen where customers could watch the chefs cooking. How would we achieve this? By having no pass: each dish would be served straight from the chef, as it comes. So it was a logical, practical process, that led to sharing plates.

Of course, there were still plenty of practical matters to sort out when making a professional kitchen into an open kitchen – the extraction system is really important, for instance, and I hate fluorescent lighting.

Tell us about Masala Zone: it’s your street-food option, and very affordable, but at the same time the latest branch is in the fantastic Criterion building in Piccadilly – another historical site right in the middle of the West End.

Well, the best Indian street food is at Chowpatty Beach in Mumbai – but if you eat it you risk getting diarrhoea. So I say that the best safe Indian street food is at Masala Zone.

But Masala Zone is much more than street food, of which we have no fewer than 18 dishes. It is also about food as eaten at home – our pioneering thalis – curries, grills and biryanis from all over India. A unique array.

The Criterion is a wonderful building, but it’s not an easy shape, being long and thin – the previous restaurants got it completely wrong. So we have made a lot of changes, and you can see how the space evolves as you walk through from one section to the next. And it is all done with decoration that floats in front of the walls, because the whole interior is listed – you can’t touch it.

(Note: Camellia Panjabi’s latest book, Vegetables The Indian Way, is published in September.)